Origins of Network Wormholes

People enjoy the company of those who are similar to themselves. However, people also form and maintain relationships with socially distant, dissimilar people. These social ties, although rare, serve the important function of bridging disconnected communities, facilitating the flow of new useful information (e.g., job openings) and integrating social groups for social solidarity and large-scale collective action.

One would probably guess that bridging ties between people who have less in common are relationally “weak” – infrequent communication, lower emotional attachment, and instrumentally motivated. However, bridging ties that span long network distances in population-scale communication networks are not as weak. A number of fascinating questions arise from closely observing these rare bridging ties. How does it matter that these bridging ties are strong? If people prefer social similarity, why do they not only maintain ties to dissimilar people, but in ways that probably require a lot of time, attention, and emotional investment?

My ongoing research tries to address these questions on the origins of bridging ties and, more fundamentally, network diversity using large-scale social media data analysis, computational models, and online experiments.

1. Network Wormholes

Abstract

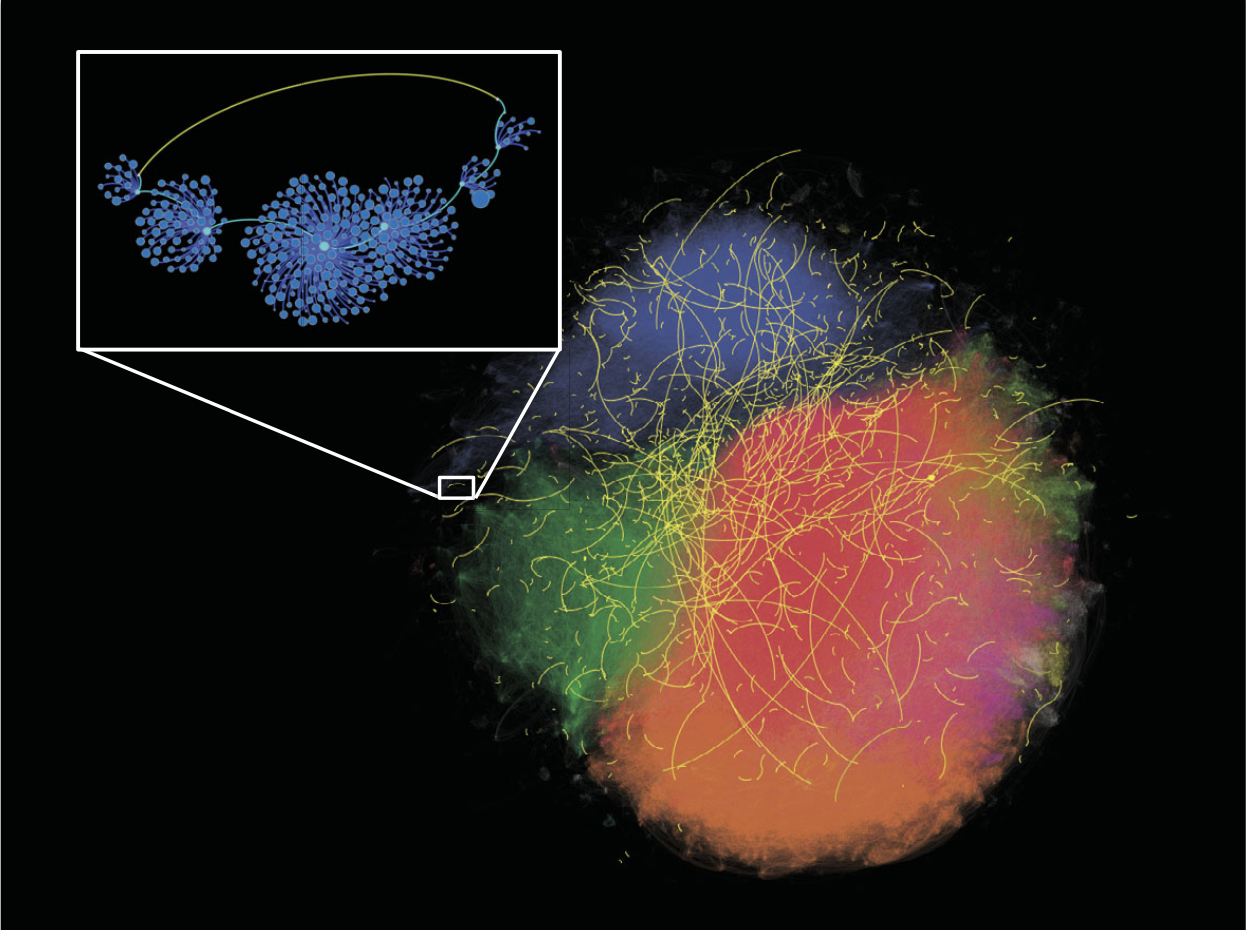

Long-range connections that span large social networks are widely assumed to be weak, composed of sporadic and emotionally distant relationships. However, researchers historically have lacked the population-scale network data needed to verify the predicted weakness. Using data from 11 culturally diverse population-scale networks on four continents—encompassing 56 million Twitter users and 58 million mobile phone subscribers—we find that long-range ties are nearly as strong as social ties embedded within a small circle of friends. These high-bandwidth connections have important implications for diffusion and social integration.

Article link: Science. Here is a short video that explains the main findings.

Dataset

For this study, I collected 158 million Twitter user accounts between 2013 and 2014 and constructed bidirected @mention networks in eight countries. The edgelists for these eight countries, with @mention frequency as weights, can be found in Harvard Dataverse.

2. Where Do Wormholes Come From?

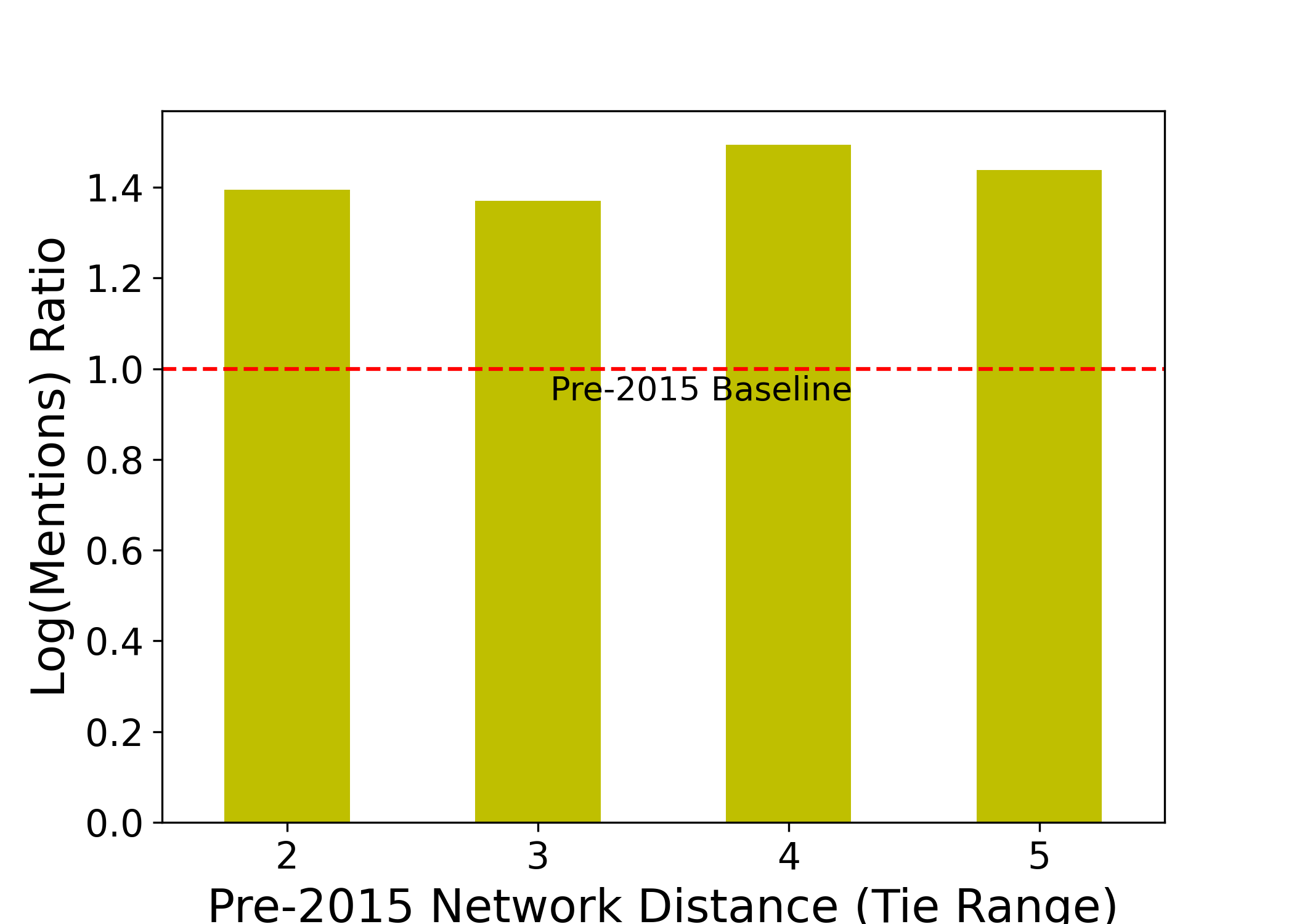

Abstract

This study examines the survival and evolution of 443K bidirectional mention ties on Twitter by merging datasets collected before 2015 and in the first few months of the COVID-19 pandemic (February to June, 2020). We hypothesize that strong pre-existing ties, marked by frequent communication and shared identities, endure and tolerate cognitive and stance differences over time. Our findings show that surviving ties are stronger than average pre-2015 ties but exhibit greater cognitive distance in COVID-19 discussions, suggesting that strong ties can tolerate different and even opposing opinions on contentious topics. This challenges traditional models of social influence and homophily, which predict increased cognitive similarity within strong ties. The findings imply the potential for old ties to function as network bridges, reducing political divides by connecting dissimilar social groups.

Article link: SBP-BRiMS